These words all look fairly similar but they’re not, of course, or I wouldn’t be talking about them.

To start off with, cote and côte are not even remotely related and not even pronounced in the same way! Cote is pronounced much like the English “cot” whereas côte is almost like “caught” but not quite. To an untrained Anglo-Saxon ear, they sound pretty much the same of course but they’re not!

Cote comes from the mediaeval Latin quota pars meaning each one’s share, which gives a whole range of derivative meanings such as a quotation on the stock market, a school grade, someone’s rating or standing (la cote de popularité du président = the president’s popularity rating (very low at the moment), elle a la cote = she’s very popular at the moment) and even dimension (as-tu pris toutes les cotes = have you taken all the measurements?).

Côte, with its circumflex indicating a dropped “s” you may remember, comes from the Latin costa meaning “flank” and has even more meanings than cote.

First we have the ribs in our body (j’ai mal aux côtes = I have sore ribs), leading to expressions such as côte à côte = side by side.

Then we have animal ribs with côte d’agneau = lamb chop, côte première = loin chop, because it’s among the first ones on the rib and côte découverte, my favourite which is the ones streaked with fat further along the rib. I don’t, however, know what they are called in English. Any suggestions?

Another meaning of côte is the sort of ribbing you get in velvet (velours à larges côtes = wide rib corduroy, velours côtelé being regular corduroy) or knitting (j’ai fait les poignets en côtes = I did the cuffs in ribbing).

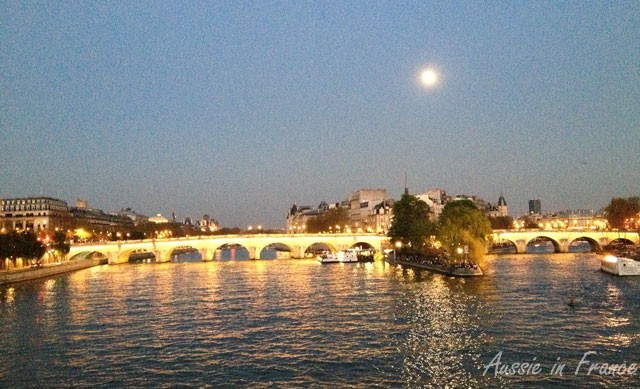

But doesn’t côte mean “coast”, I can hear you saying. How do you get from rib to coast? Well, the coast flanks the sea or ocean, doesn’t it? So we have Côte d’Azur = the French Riviera. Also, there is no separate word for coastline. Une côte rocheuse = a rocky coastline while a coast road = une route qui longe la côte but more often than not it is called une corniche (or route en corniche).

An entirely different meaning, but still attached to the idea of flank, is slope or hillside. This is one you need to know when you’re cycling (si la côte est trop dure, je descends du vélo = if the hill is too steep, I get off my bike).

A hillstart in a car is un démarrage en côte.

But coteau also means a slope or hillside and can even mean a hill only it’s not used in the same way.

A coteau is a hillside or slope on which vineyards are grown to start with. You may remember some really steep ones we saw in Germany this summer along the Moselle. Les vignes poussaient tout au long du coteau = There were vines growing all along the hillside/slope BUT Je suis arrivée en haut de la côte sans m’arrêter = I got to the top of the hill without stopping (yes, it does happen!)

In fact, the slopes on either side of a river are always called coteaux. Il habite sur le coteau = He lives on the side of the hill and not Il habite sur la côte which means he lives on the coast. Now, isn’t that confusing?

The only way I can really explain is that coteau gives the idea of a surface area whereas côte indicates height. I think the first and last photos illustrate the difference well. Are you with me?