Even French people confuse gîte and chambre d’hôte. I know this for certain because when I tell people I have a gîte they often start talking about le petit déjeuner which, of course, is only served in a B&B.

Before it came to mean a self-catering cottage in the country, gîte, which comes from the verb gésir, derived from the Latin jacere (to lie down), meant any place to sleep either permanently or temporarily.

Offrir le gîte et le couvert, for example, means to offer board and lodging.

A gîte, I have just learnt, is also a resting place for hares. Ten points to anyone who knows the equivalent in English! I certainly didn’t. “Hares do not bear their young below ground in a burrow as do other leporids, but rather in a shallow depression or flattened nest of grass called a form. All rabbits (except the cottontail rabbits) live underground in burrows or warrens, while hares (and cottontail rabbits) live in simple nests above the ground, and usually do not live in groups.” Thank you Wikipedia. And thank you Susan from Days in the Claise who has posted a photo of a form.

A mineral deposit is also called a gîte, as in gîte de zinc but an oil deposit is a gisement de pétrole. And pétrole is not petrol as we say in Australia for gasoline – you fill your car with essence in France. Pétrole means oil or petroleum. Diesel engines take gas-oil or gazole (pronounced gaz-well, don’t ask me why!)

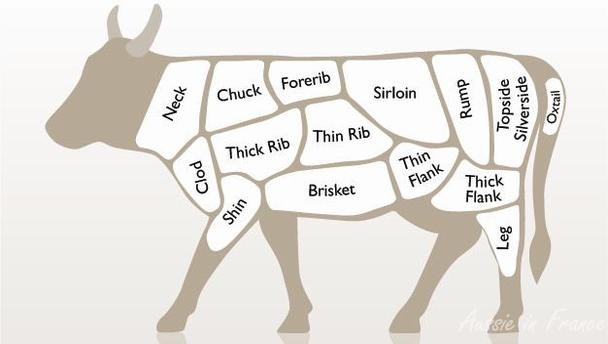

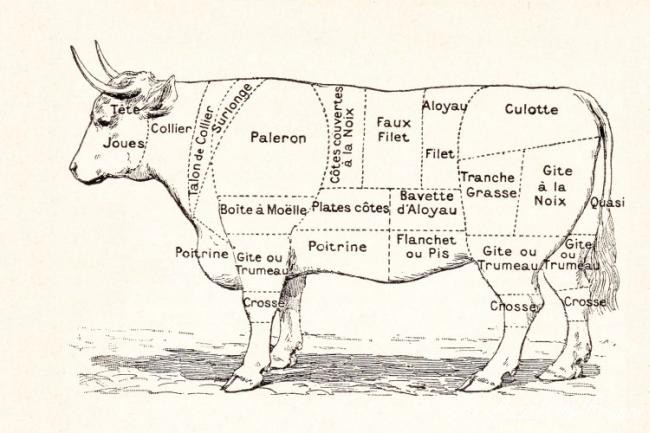

Gîte (short for gîte à la noix) is also a cut of beef corresponding more or less to what we call topside (UK) or bottom round (US). French and English butchers don’t cut up beef in the same way so quite often there is no real equivalent (entrecôte, côte de boeuf, T-bone, etc.), as you can see from the drawings. You can read more on the subject in Posted in Paris.

Another expression with the verb gésir is Ici gît le roi d’Espagne (here lies the King of Spain). Other examples are: un trésor qui gît au fond des mers = A treasure lying on the bottom of the sea and ses vêtements gisaient sur le sol, a somewhat literary way of saying that his clothes were strewn all over the floor.

So now you know the difference between a gîte and a chambre d’hôte – and a lot more useful things besides!