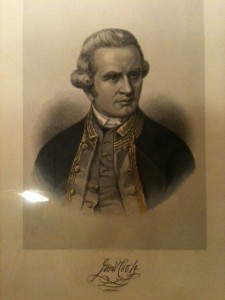

I’ve been reading Hough’s biography of Captain Cook and thinking about what Townsvillean said when I told him we’d bought a house in Blois built in 1584: “Your house is about twice as old as my nation!”.

I’ve been reading Hough’s biography of Captain Cook and thinking about what Townsvillean said when I told him we’d bought a house in Blois built in 1584: “Your house is about twice as old as my nation!”.

One of the amazing things to me about Cook is that he didn’t know he had discovered Australia. I find it very hard to understand how someone with such intimate knowledge of map making could have sailed up 4,000 kilometers of unknown coastline and still not realised he had discovered Terra Australis. He even sailed past Magnetic Island, my very favourite coral island, calling it that because his compass went haywire. But he made two other voyages in an endeavour (unintended pun) to find the Great Southern Land, but to no avail. Instead, he got killed in a skirmish in Hawaii in 1779 at the age of 50. He’d been at sea for nearly three years.

He first sighted Australia in 1770 as we all know. The first convicts arrived in 1788 and a mottley crowd they were. It was survival of the fittest. The First Fleet consisted of 11 ships carrying about 1400 people and it took 8 months to get there. They lost about 70 on the way. A little over half of the first settlers were convicts.

He first sighted Australia in 1770 as we all know. The first convicts arrived in 1788 and a mottley crowd they were. It was survival of the fittest. The First Fleet consisted of 11 ships carrying about 1400 people and it took 8 months to get there. They lost about 70 on the way. A little over half of the first settlers were convicts.

Now what was happening in France at the time?

1770. Mild winter. Cool spring. Heat-shrivelled wheat in May and June. Catastrophic harvest. A hailstorm of exceptional violence that devasted all the cereal crops from the Loire to the Rhine on 13th July. Drought in the south. An early wine harvest. Some authors believed that the disastrous weather spurred on the French Revolution which took place the next year.

We all know the story of Marie-Antoinette who, when she heard there was no more bread for the poor, replied « Then give them cake! » It was actually brioche which is just as naive and very indictive of the great gulf that separated the people who had just set foot on Australian soil from the ruling classes. In France, a bloody revolution and a guillotine were needed to break the bonds of servitude, which meant brains and education. In Australia, a more native cunning was needed to survive combined with perseverance and endurance.

The effects of the French Revolution didn’t last long. Just ten years later, Napoleon was First Consul and in 1804, he became Emperor. There was no longer royal blood in power but you could hardly call it democratic. In 1804 in Australia, Irish convicts launched the Castle Hill Rebellion. 51 were punished and 9 hanged. In the same year, the settlement that was later to become Hobart was founded at Sullivan’s Cove.

1815 saw the defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo and the start of a constitutional monarchy but it was not exactly plain sailing. In Australia, the road over the Blue Mountains, first crossed in 1813 by Lawson, Blaxland and Wentworth, was completed to the Macquarie River. 1848 saw the proclamation of the second republic in France and the beginning of the Second Empire with Napoleon III. Meanwhile, back in Australia, that was the year Ludwig Leichhardt the explorer disappeared on the Darling Downs.

The French empire finally came to an end in 1870. In the same year, Western Australia, Victoria, Queensland, New South Wales and South Australia each adopted its own flag. On 1st January 1901, Australia became a nation. Queen Victoria, also the Queen of Australia died on 22nd January after 64 years on the throne. By 1908 women had the vote in every State. Would you believe that French women didn’t enjoy that basic right until 1944!

France then suffered horrendous losses, both in lives and heritage during two world wars. Australia also lost many lives particularly in proportion to its population. It gets me terribly upset to see the aftermath of war in France, where whole villages and towns were completely wiped out and were rebuilt as quickly as possible to house the remaining population. This is particularly obvious in some parts of Normandy and Brittany.

Since then, both countries have forged ahead with far more similar paths. I wonder what present-day characteristics of the French and the Australians can be attributed to these different events in history.

Captain James Cook: A Biography by Richard Alexander Hough (W.W. Norton & Company, 1997)

The suburb of Lapérouse is situated on the northern headland of Botany Bay. It was here that the eponymous navigator (a great french admirer of James Cook) spent many weeks as part of his exploration of the south Pacific. Commissioned by Louis XVI he arrived at Botany Bay within days of the First Fleet (1788). It’s a pretty nice spot. I believe that relations between the French and British were quite cordial at the time – they were both a long way from home!

He’s hardly mentioned in the biography but I’m about to read Cook’s journals so that should give me more information. The French are very proud of Lapérouse of course. He was probably their greatest navigator.

Very interesting, thanks for this!

It isn’t very well known but the French explored and mapped a great deal of the Western Australian coastline. Almost 200 places in Western Australia still have these French names

Hi Sharon, I had no idea that there were so many places in WA with French names!

One of greatest french navigators is Jacques Cartier (1491-1557) who discovered Canada in 1534. The link between French and Canadians is still very strong today, as you probably know.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jacques_Cartier

Amongst the most famous you can add

– Bougainville (1729-1811) mapped and established the first settlement on the Falkland Islands (1764) in what is today Port Louis (named after the king Louis XV). he also gave his name to Bougainville island (New Guinea) in 1768. The flower Bougainvillea was named after him.

– Dumont d’Urville (1790-1842) he was one of the first to spot the “Venus de Milo” and had it acquired by the French government. He visited NZ, AU, NG and collected a vast amount of plant, did a lot of mapping. He also went to the Antartic..

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jules_Dumont_d%27Urville.

There are many others but these 4 (including La Perouse) are probably the most famous…

i am reading capt. James Cooks journals

i hope you enjoy them!

My interest is in the influence the French Revolution had on the fledgling penal settlement at New South Wales.

King George III was experiencing health problems at the same time as Phillip was experiencing insubordination from his marines at the new colony.

“Phillips relationship with the marines was often poisonous but it later became farcical when he instituted a night watch of twelve worthy convicts to prevent robberies from the public stores and vegetable gardens.”[1]

In 1792 Phillip returned to England and Major Grose assumed command reversing many of Phillip’s policies[2]. It was the beginning of a military coup by stealth which came to a head with the 1808 rum rebellion and the deposing of Governor Bligh.

I suspect that the coincidence of George’s illness with the pressures of a simultaneous French revolution distracted attention away from developing complications at the penal colony thereby contributing to the ongoing rebellious culture within the military.

It is challenging to think that the ‘bad press’ suffered by the convicts over the years really belonged with the insubordinate military and their culture of corruption.

1. Pembroke, M. ‘Arthur Phillip, Sailor, Mmercenary, Governor, Spy’ p199

2. wikipedia.org/wiki/New_South_Wales_Corps